In an interview discussing the development of Crash Bandicoot on the original PlayStation, Andy Gavin describes how the team rendered richer environments, higher-resolution textures, and smoother animation than any other game on the platform at the time.

Most PlayStation games followed a predictable path. Before each level the game loaded all the assets from the CD into memory. The budget was tiny: 2 MB of system RAM and 1 MB of VRAM. Once the level started the CD was mostly used for music.

This approach left performance on the table. During gameplay only a small portion of a level is ever visible. Large amounts of data were loaded despite never contributing to the final image.

Crash Bandicoot broke from this model by decomposing levels into fixed-size pages and treating them as virtual memory. A precomputed visibility layout determined which pages were required for each region of the level. As long as the working set of pages fit in memory, streaming remained continuous and transparent to the player.

In practice, the system was no longer constrained by total RAM capacity but by the amount of data that could be packed into a single page. The effective size of a level became the space allocated to it on disk rather than the size of main memory.

The same constraint still governs modern rendering engines. Hardware capabilities have evolved but GPUs remain bounded by how much data they can access efficiently at any given moment.

Both scenes run on the original PlayStation. Crash streams level data aggressively, enabling denser textures and more visual variety. Tomb Raider relies on traditional loading.

The same constraint appears in scientific visualization. At Biohub, some of our work involves building interactive systems for visualizing large, multi-dimensional bioimaging datasets that exceed GPU memory by orders of magnitude.

Virtual texturing is a natural fit for this problem. However, existing explanations gloss over details, particularly around residency and feedback. Implementing a complete prototype exposed gaps in how the system is commonly described.

This article examines the problem virtual texturing solves, the tradeoffs it introduces, and how the system operates in practice.

Big Textures

When dealing with large open-worlds or bioimaging data, we want massive textures that preserve fine detail. These textures often do not fit in VRAM. Even if the GPU could hold them moving data of that size across the bus is impractical. Memory bandwidth collapses long before capacity does.

The limiting factor when rendering large textures is not memory or bandwidth, but screen resolution. Because a screen has a fixed number of pixels, only the portion of a texture that projects onto the screen can contribute to the final image.

Suppose you have a 24k texture projected onto a 4k display. The texture is six times larger so it can never be seen at full resolution all at once. Zoomed out the screen downsamples it and only a fraction of the pixels contribute to the image. Zoomed in more detail becomes visible but only over a small region at a time.

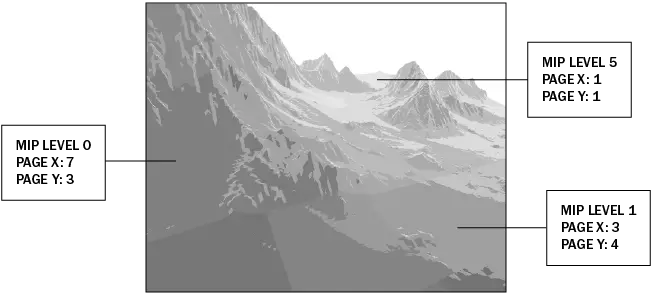

Most systems leverage this constraint by converting the texture into a mip chain and splitting each mip into fixed-size pages1. At runtime, the system determines which pages are needed and streams only those pages to the GPU.

Designing a runtime system is straightforward when a texture is rendered in 2D. At any given moment only a single mip level is active along with a small set of pages. LOD selection reduces to picking that mip. Each page can be rendered as a tile using its own draw call.

This is the model used by systems like Google Maps or Microsoft Deep Zoom. There is nuance at scale, such as streaming pages over the wire, reducing draw calls, and handling filtering across tile boundaries, but conceptually the system remains easy to reason about. This simplicity breaks down in 3D.

In 3D multiple mip levels must be sampled at the same time. Surfaces close to the camera require high-resolution pages while distant geometry samples from lower-resolution ones. LOD selection has to happen per pixel.

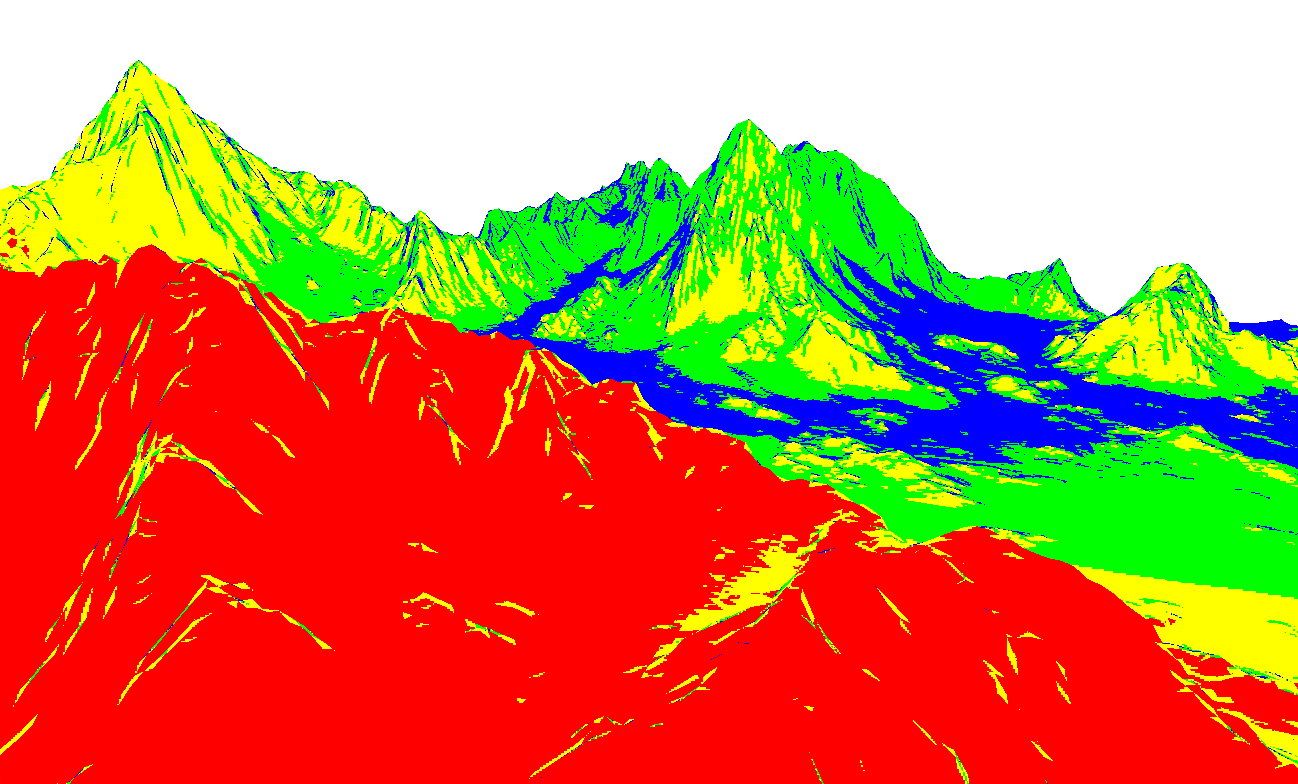

- mip0

- mip1

- mip2

- mip3

Colors indicate mip level, with red marking the highest resolution and blue the lowest.

The usual workarounds involve splitting geometry, binding multiple textures, and manually managing LODs. These approaches stress the GPU in all the wrong ways for real-time rendering. Texture binds multiply. Draw calls explode. Bandwidth usage spikes. You spend more time feeding the GPU than rendering.

This is the exact bottleneck virtual textures are designed to eliminate.

Virtualizing Textures

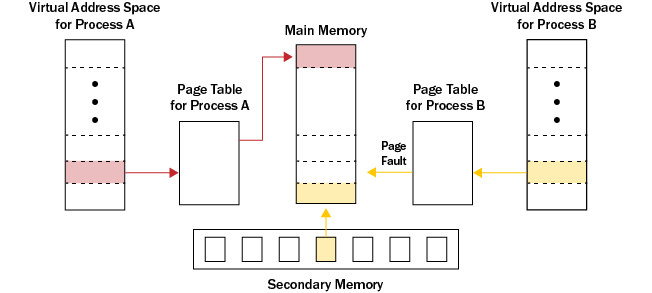

CPUs solved the “too much data, not enough memory” problem decades ago with virtual memory. Every program believes it owns a contiguous address space. That belief is an illusion. The addresses a program uses are virtual, not physical.

Physical memory is fragmented and constantly changing. Virtual addresses are translated to physical ones through a page table. This indirection underpins modern memory management, but the part that matters here is that it lets programs pretend they have more memory than actually exists.

When RAM runs out the operating system can move inactive pages to disk. If a program tries to access a page that is not resident, a page fault occurs: the OS loads the missing page back into memory, updates the page table, and execution resumes. There is a cost to this, but the system is designed to make such faults rare.

Virtual texturing applies this approach to textures. A massive texture is exposed to the application, but only the pages required for the current view are kept in GPU memory, often just a few megabytes, with residency tracked explicitly through a page table.

This solves both sides of the problem. You never allocate the full-resolution texture and you limit bandwidth by uploading only the texels the screen actually samples. The indirection untangles LOD selection in 3D:

- A mesh samples from a single unified virtual texture.

- Texture binds collapse to one physical texture.

- High- and low-resolution pages coexist in the same address space.

The CPU and operating system give you virtual memory for free. On the GPU, modern engines still build it themselves. Even with hardware support for sparse textures, engines manage their own page tables, residency logic, and streaming systems. That is virtual texturing.

Building the System

The implementation details below are based on a working prototype I built. You can explore the source here.

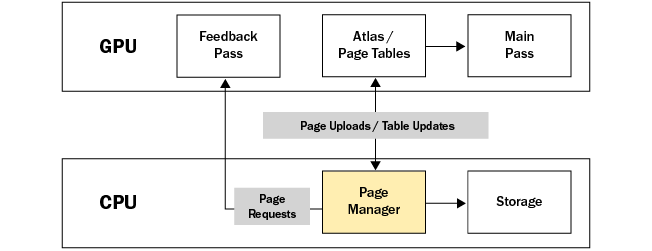

Virtual texturing is not a single shader. It is a system. Multiple components work together across the CPU and GPU to make massive textures appear fully resident while only a small fraction of it actually occupies GPU memory.

Each frame the system must answer three questions:

- Addressing: where each texel should be sampled from.

- Feedback: which virtual pages were accessed and at what resolution.

- Residency: which pages must be present in GPU memory.

These concerns are deliberately separated. Addressing happens entirely on the GPU during rendering. Feedback observes sampling behavior without interfering with it. Residency decisions are made on the CPU, where policy, caching, and I/O can be managed explicitly.

The following sections break these components down in isolation before tying them back together into a closed loop.

Virtual to Physical Coordinates

In the same way that virtual memory presents a program with a contiguous address space, virtual texturing presents a single contiguous texture space. From the application’s point of view UV coordinates span the full-resolution texture. In reality, the data backing those coordinates is partially resident and changing.

At any moment only a small subset of the texture data exists in GPU memory. The rest remains addressable but non-resident. Bridging this gap requires separating how texture data is addressed from where it is physically stored.

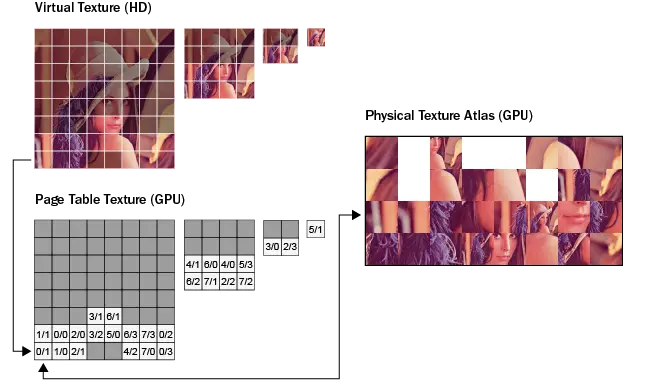

The system operates over three representations of the same texture: a virtual texture defining the full address space, a page table translating virtual pages and tracking residency, and a physical texture atlas storing the pages currently resident in GPU memory.

During the main render pass the GPU samples exclusively from the physical texture atlas. Texture lookups begin in virtual texture space, but before any texel can be fetched, the virtual address must be translated. That translation is performed through the page table.

A page table is a GPU resource typically implemented as a 2D texture. Each texel in the page table corresponds to a single virtual page. Conceptually, there is one page table per mip level. In practice, these tables are often packed into a single texture by reusing mip levels to mirror the virtual mip hierarchy.

The page table stores metadata, not color data. Each entry encodes whether the page is resident and where the page is located within the physical texture atlas.

A common approach is to pack this information in a single 32-bit integer, keeping the table small and cache-friendly, which matters because it’s sampled for every texture lookup. For example:

The exact bit layout is not important. The only requirement is that the CPU and GPU agree on the encoding. Additional bits can be repurposed for LOD hints, eviction state, or debugging.

The page table does not decide what should be sampled. It only answers whether a page is resident and where it lives. Sampling itself happens entirely at sample time: estimating footprint, selecting a mip level, resolving the virtual page, and remapping the lookup into the atlas.

For regular textures the GPU selects the mip level automatically. Virtual textures cannot rely on this behavior because residency is managed explicitly. The shader must compute the mip level manually using screen-space derivatives2:

Once the mip level is known, the dimensions of the virtual page grid at that level follow directly from the virtual texture and page sizes. The base level contains

Virtual coordinates are first scaled by the page grid resolution at mip level

The virtual page index

Combining the physical page index with the local page offset yields the sample location in atlas page coordinates. Scaling by the ratio of page size

The GPU then samples the physical texture atlas directly.

The full lookup path: mip selection, page table lookup, and address translation, can be expressed in a single shader function:

const uint PAGE_MASK = 0xFFu; // 8 bits per axis

vec4 SampleVirtualTexture(vec2 uv) {

uv = clamp(uv, 0.0, 1.0 - 1e-7);

vec2 dx = dFdx(uv) * u_VirtualSize;

vec2 dy = dFdy(uv) * u_VirtualSize;

float footprint2 = max(dot(dx, dx), dot(dy, dy));

int mip = clamp(

int(floor(0.5 * log2(max(footprint2, 1e-8)))),

u_MinMaxMipLevel.x,

u_MinMaxMipLevel.y

);

vec2 pages = max((u_VirtualSize / u_PageSize) * exp2(-float(mip)), vec2(1.0));

vec2 page_coords_f = uv * pages;

ivec2 virtual_page = ivec2(floor(page_coords_f));

vec2 page_uv = fract(page_coords_f);

uint entry = texelFetch(u_PageTable, virtual_page, mip).r;

if ((entry & 1u) == 0u)

return vec4(0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0); // fallback omitted

ivec2 physical_page = ivec2(

int((entry >> 1) & PAGE_MASK),

int((entry >> 9) & PAGE_MASK)

);

vec2 atlas_uv = (vec2(physical_page) + page_uv) * u_PageScale;

return textureLod(u_TextureAtlas, atlas_uv, 0.0);

}This translation path guarantees that the shader always produces a valid sample. When the ideal page is missing, the fallback makes the absence explicit. Determining which pages should become resident is handled by a separate feedback pass which we cover next.

Feedback Pass

If we tried to record feedback in the main pass every fragment would emit writes, destroying the nice read-only behavior of sampling and scaling cost with pixels instead of unique pages.

Virtual texturing systems avoid this by introducing a separate feedback pass. The scene is rendered to a reduced-resolution off-screen target that produces a compact summary of which virtual pages are required and at which mip levels. Precision is traded for scalability while preserving the information needed to drive residency decisions.

Like the page table, the feedback pass stores metadata. Each feedback entry records a virtual page index and the mip level at which it was sampled, packed into a compact binary representation.

Each shade of gray represents a distinct virtual page. Brighter regions correspond to coarser mip levels.

The computation required to generate this information closely mirrors the sampling shader. The feedback pass manually computes the mip level from screen-space derivatives and converts virtual coordinates into virtual page indices using the same math.

The difference is that no texture sampling occurs. Once the virtual page index and mip level are known, they are written to the feedback buffer for later processing.

const uint MIP_MASK = 0x1Fu; // 5 bits for mip level (0–31)

const uint PAGE_MASK = 0xFFu; // 8 bits for page index per axis (0–255)

uint EncodeFeedback(vec2 uv) {

uv = clamp(uv, vec2(0.0), vec2(1.0) - vec2(1e-7));

// select mip level (same logic as SampleVirtualTexture)

vec2 dx = dFdx(uv) * u_VirtualSize;

vec2 dy = dFdy(uv) * u_VirtualSize;

float footprint2 = max(dot(dx, dx), dot(dy, dy));

int mip = clamp(

int(floor(0.5 * log2(max(footprint2, 1e-8)))),

u_MinMaxMipLevel.x,

u_MinMaxMipLevel.y

);

// page grid at mip

vec2 pages = max((u_VirtualSize / u_PageSize) * exp2(-float(mip)), vec2(1.0));

// virtual page index

vec2 page_coords_f = uv * pages;

ivec2 virtual_page = ivec2(floor(page_coords_f));

uint mip_bits = uint(mip) & MIP_MASK;

uint page_x = uint(virtual_page.x) & PAGE_MASK;

uint page_y = uint(virtual_page.y) & PAGE_MASK;

return mip_bits | (page_x << 5) | (page_y << 13);

}After the feedback pass completes the feedback buffer contains a set of page requests: the virtual page indices and mip levels required to render the current view. This buffer forms the handoff point between rendering and residency management. What happens next is a policy decision.

Page Manager

Feedback reports what was touched. The page manager decides what to do about it.

The page manager is a CPU-side orchestrator responsible for turning page requests into residency changes. It consumes feedback, loads missing pages, allocates space in the texture atlas, uploads page data, and keeps the page table up to date.

Once the feedback pass completes, the page manager decodes the feedback buffer using the bit layout defined in the feedback shader. For each unique request, it checks the page table to determine whether the page is already resident.

Requests then fall into two categories:

- If a page is already resident, it is marked as "used" for the current frame.

- If a page is not resident, the page manager issues an asynchronous request to load the page data from storage.

Marking pages is where policy enters the system.

When page data becomes available the page manager must decide where it should live in the physical texture atlas. Atlas space is limited so allocating a slot may require evicting an existing page.

Most virtual texturing systems implement an LRU-style cache which aligns well with the spatial and temporal coherence of typical camera movement.

In its simplest form, the cache manages a fixed set of page slots identified by

A common approach is to pin certain pages so they are never evicted. Pages at the lowest level of detail are typically pinned to guarantee that there is always valid data to sample.

Pinning prevents holes in the texture but must be used sparingly. Overuse increases visible popping and reduces cache effectiveness. In a well-tuned system, pinned pages serve only as a safety net rather than a steady-state solution.

The feedback pass and page manager form a closed loop. The renderer observes access patterns, the page manager adjusts residency to match. When page delivery keeps up with demand the system converges toward the ideal working set.

When it does not, the system degrades gracefully. Lower-resolution pages are sampled, requests accumulate, and residency catches up over subsequent frames. This behavior is what makes virtual texturing practical despite its complexity.

Virtual Textures in Practice

Virtual texturing moved from white papers to shipping code with John Carmack’s work on id Tech 5 where the technique was known as MegaTexture. Unlike modern engines which treat virtual texturing as an optional optimization, id Tech 5 made it the only texturing path. Every surface in the static world sampled from a single virtual address space.

This approach eliminated the need to bind discrete textures per draw call. Visibility was resolved through a feedback pass that recorded which virtual pages were accessed, and only those pages were streamed into a fixed-size physical cache. GPU memory usage remained bounded regardless of world size.

The result was visually striking. Repeating tile patterns disappeared, and artists could paint unique detail across large environments without concern for reuse. The primary cost was not GPU throughput, but latency elsewhere in the system.

id Tech 5’s fully virtualized texturing pipeline as shipped in Rage on Xbox 360.

Virtualization shifted pressure onto the CPU and I/O stack. Transcoding threads competed for time, and seek latency delayed page delivery. When the working set exceeded capacity, delayed page uploads resulted in visible texture pop-in.

id Software moved away from fully virtualized texturing in subsequent engine iterations but the underlying idea persisted.

Modern GPUs support virtualized texture addressing directly in hardware through sparse textures, where page table translation is handled in silicon and resource allocation is decoupled from physical residency.

Sparse textures provide efficient address translation and managed page tables but they avoid defining policy. They do not decide which pages to load, when to evict them, or how feedback is generated. Support and behavior vary across GPUs.

Most modern engines implement their own virtual texturing systems on top of available hardware features. Engines prioritize explicit control over residency, feedback, eviction, and cross-platform determinism, treating hardware support as a mechanism rather than a complete solution.

In practice, virtual texturing is effective only in narrow, data-dominated scenarios where texture size vastly exceeds GPU memory. For the majority of real-time workloads traditional textures offer better performance and faster iteration.

Virtual texturing is not a general upgrade path. It is a specialized technique for cases where bandwidth and memory constraints leave no viable alternative.

Crash Bandicoot followed this principle in 1996 by aligning data residency with what could be visible at any given moment. Many console games adopted similar strategies, enabling richer worlds within fixed hardware budgets.

Modern game engines push this concept more aggressively with tighter feedback loops. Contemporary techniques such as virtual geometry follow the same pattern3. Systems like Nanite blur the line between real-time and offline rendering by loading and processing only geometry that contributes to the final image.

In scientific visualization the data is different but the constraint is the same: gigantic volumes, tiny working sets. Virtual texturing turns this into a tractable problem. Once data access is virtualized, rendering multiple channels reduces to a single ray-marching pass over a consistent address space, with resolution adapting automatically to what is visible.

The key takeaway is that performance limits are rarely defined by total data size alone. They are more often defined by physical bottlenecks such as screen space, visibility, and perceptual resolution. Effective systems are built by structuring data so that only what can be observed at a given moment must be present.

Virtual texturing is one instance of a broader pattern: expose a large virtual space, maintain a small working set, and let the system constantly reconcile the two.

Footnotes

-

In large-scale biomedical imaging, data is often stored in formats like OME-Zarr that natively encode multi-resolution chunked n-dimensional data, enabling clients to request only the regions and resolutions needed for the current view. ↩

-

For a deep dive into how GPUs select mip levels using screen-space derivatives see “Mipmap Selection in Too Much Detail”. It walks through the process in detail and is a useful reference. ↩

-

The idea predates Nanite. Carmack discussed virtualized geometry as a successor to MegaTexture during the id Tech 6 era, but left id Software to focus on Oculus Rift before such work could ship. ↩